Where Has Hospitality’s Talent Gone, and Why?

- By Harri Insider Team | July 29, 2021

COVID-19 exposed many flaws in the hospitality industry’s labor supply and operational processes. The bubble burst so rapidly and so suddenly that businesses scarcely had time to react. Our Founder and CEO, Luke Fryer, recently spoke about this in a Hospitality State of Labor webinar, analyzing the full spectrum of today’s hospitality laborscape.

But before we look at challenges in workforce management, it’s important to understand where the talent went, and why. Did they leave willingly or were there other forces at work? The answer is both as the pandemic accelerated already-present labor challenges rooted in the hospitality industry and outside geopolitical factors came into play.

Talent supply patterns disrupted by geographic changes

It’s no secret that the world shut down during COVID-19. Record numbers of people moved out of populated urban areas and into the suburbs as individuals sought safety from the virus. But high populated cities are also home to large numbers of restaurants, and the migration out of these cities also meant the displacement of talent who once operated in these businesses.

So as takeout and delivery orders skyrocketed, thanks to an increased avoidance of crowded grocery stores, restaurants found themselves with fewer workers to handle increased orders.

And let’s not forget the disruption of seasonal patterns that provided temporary boosts to hospitality businesses. Schools and higher education facilities, which tend to be located near restaurants to accommodate lunchtime needs, were closed for extended periods of time. Tourism essentially screeched to a halt.

Everyday activities and milestones were paused. That meant birthdays, graduations, gametime drinks, workplace happy hours, family gatherings, and so much more, stopped almost evernight. High-traffic locations that once employed large teams to handle the capacity of such events suffered major losses.

Naturally, that all led to a decreased need for staff associated with reservation planning, wait service, and even bartending. Restaurants were forced to lay off staff in order to keep the business running. And as these urban businesses let go of their employees, those workers were encouraged to either try their luck in suburban markets or move to entirely new industries.

The impact of immigration on hospitality

While COVID-19 in itself was a massive trigger for the stopping of both US and UK immigration, both markets were facing pre-pandemic political climates that deepened immigration slowdown and placed heavy restrictions on the processing of immigrants.

We’ll dive into the numbers in a moment, but it’s important to understand the significance of decreased immigration on the hospitality industry.

As one of the most diverse labor markets out there, a large portion of frontline hospitality is composed of immigrant workers, documented or otherwise. In the US, that means migrants from countries along the southwestern border. UK restaurants, on the other hand, especially benefit from outside labor from counties in the EU.

US immigration impacting hospitality labor

Immigration policies to enter the US for extended periods of time, word on the books, and eventually become a citizen were never cut and dry. When the Trump administration came into power in 2017, anti-immigration efforts disrupted these already complex processes to slow down immigration into the country.

This also included apprehension and removal of immigrants already in the United States as well as additional policing of those attempting to enter the country illegally.

From 2016-2019, ICE investigations increased from 4,330 to 10,939. Regarding apprehensions, from 2017-2019, the Department of Homeland Security increased from 461,540 to 1,013,539, while the US Border Patrol increased from 310,531 to 851,508.

This culminated into a 2.1% increase of determinations of inadmissibility from 2018-2019 from the Office of Field Operations as well as nearly a 110% increase in Notices to Appear from 2018-2019 — documents that outline an immigrant’s legal reasons for removal out of the country.

All in all, immigrant labor from Mexico and the Northern Triangle of Central America took a huge hit at the tail end of the decade, disrupting a vital talent source for the early 2020s.

UK immigration impacting hospitality labor

Brexit had a rocky timeline, but the United Kingdom formally left the EU on January 31, 2020. When it went into effect, free movement of UK and non-UK people would be suspended and replaced with a points system and a new visa program.

For someone in the EU to work in the UK, they need a visa which can be achieved at 70 points. Points can be earned by being a fluent English speaker, reaching or exceeding a position-specific salary threshold, earning PHDs, having a job offer from a sponsor, having a job offer at a required skill level, and other similar achievements.

They also will need to be sponsored by an employer that applied for and received sponsorship eligibility. To add further restrictions, the new visa program raises the age limit from 16 to 18.

While Brexit certainly does make job-based immigration possible, it favors “high-skill” jobs over what typically would be considered a frontline hospitality position. And because hospitality professionals tend to start at a younger age, the two-year eligibility increase cuts off a significant pool of potential workers.

In 2019 just before Brexit went into effect, approximately 871 immigrants entered the UK while almost 2,500 left the country, signaling a mass decline in the hospitality workforce even before new visa restrictions were put into place. As of July 2, 2021, the UK saw 5.6M applications for settled status in wake of the post-Brexit scheme deadline, with an estimated 3.7M EU nationals living in the UK.

Hospitality training and graduates trending downward

Anecdotally we know that enrollment into the culinary arts has been a concern dating back to 2017. The Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System showed that culinary schools saw degree completion decline by 8,000 from 2012-2017, with a total of 16,792 culinary school degrees awarded in 2017.

There are multiple reasons for this decline. The restaurant industry was always in a state of labor crisis, adding an element of increased job instability. Rising tuition costs coupled with a downturned economy may have led to increased instances of students opting out of school altogether or pursuing general degrees at local colleges — rather than professional culinary degrees.

This is especially true when you consider the rise of at-home and bakers in the wake of social media. That’s not to say becoming a restaurant professional without formal training was an easy feat, but it certainly became more accessible as at-home businesses grew.

Naturally, COVID-19 resulted in further decreases in university enrollment numbers as students in all industries across the globe put a pause on schooling. Yet despite this being a widespread issue, hands-on fields like the culinary arts were impacted even more strongly. You can’t effectively teach the culinary arts over a webcam or online course. The right training, from food preparation to management, requires an in-person touch and experience in the field.

Hospitality may be adapting to COVID-19 and discovering ways to operate while maintaining high levels of safety, but that doesn’t mean students will be so keen to return, especially if they moved on to schooling in new industries.

Restaurant operators must recapture the imagination of young professionals to help them envision hospitality as not just a job, but a career. Tuition assistance programs for agriculture or culinary arts programs have been on the rise from brands like Chipotle and McDonald’s, and we may continue to see this trending upwards in an attempt to bring long-term talent back into the industry. Until then, culinary graduate shortages will continue to play a major role in the labor shortage until more supply is added to the talent feeder.

Hospitality pushed, other industries pulled

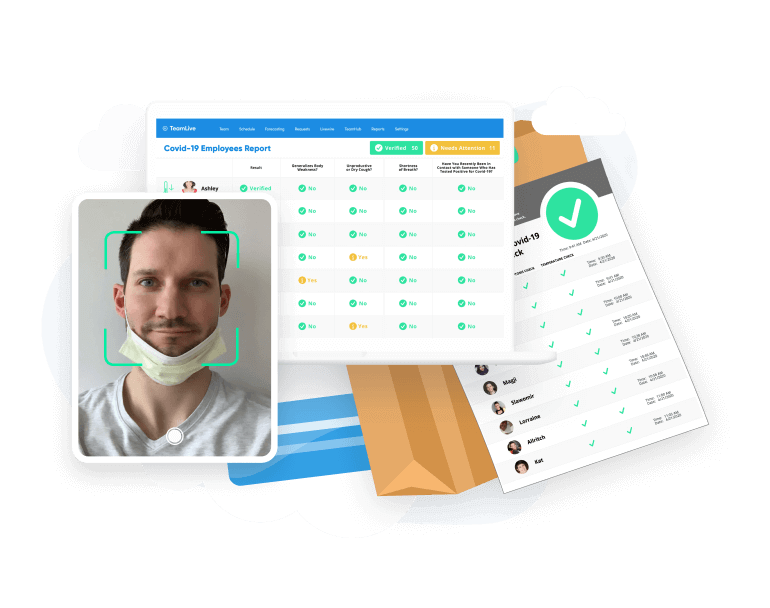

As workers were driven away from the hospitality industry, intentionally or not, surging industries, specifically tech-savvy sectors took advantage of the displaced talent. COVID-19 restaurant shutdowns, safety concerns, and economic turmoil drove workers away from the industry. When restaurants were finally able to increase operational capacity, workers were reluctant to return.

Miscommunication or lack of communication surrounding furloughs, layoffs, masking policies, sanitation procedures, and guest interactions in the wake of the pandemic drove a rift between restaurants and employees. Workers felt burned by their managers or burned out from the confusion.

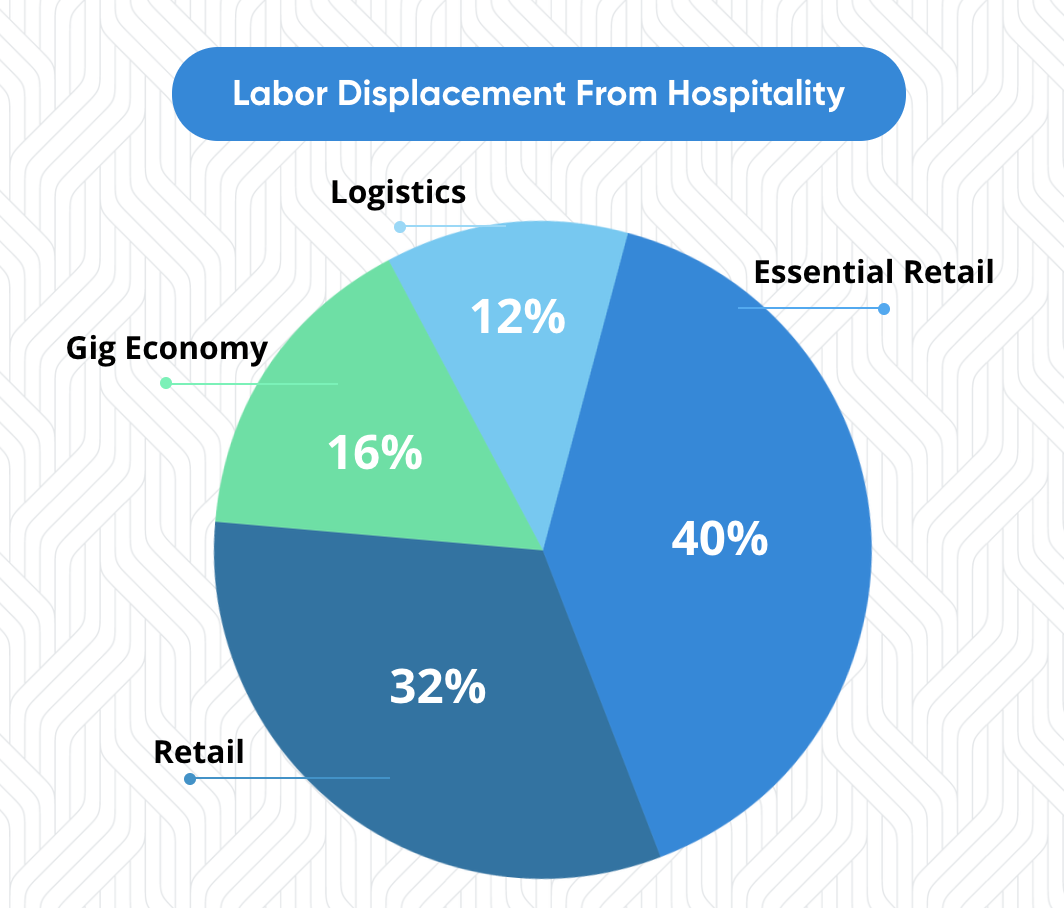

Many employees that left under these circumstances were especially reluctant to return to hospitality. According to our Labor Crisis Conditions and Sentiments Report, retail, logistics, and the gig economy were the primary ‘destinations’ for hospitality employees. A significant portion of these employees are unwilling to return.

And what drove these moves? Priorities shifted as COVID-19 put an emphasis on our health, especially those caring for children, the elderly, or immunocompromised individuals. For others, vaccine mandates that grew in popularity amidst the hospitality industry proved intrusive. Workers flocked to jobs that could offer predictable and/or flexible schedules, the ability to work from home, better healthcare, and stronger compensation.